Entering Antoine Schneck’s Parisian studio is a troubling, or frightening, or exciting, or comforting experience, or a bit of all of these at once.

Against the walls lie huge stone lying figures, cars or armour, on a table of fishing flies, hanging portraits of heads without bodies, not cut off from the body, just without the body.. They are huge faces that float and take hold of you. In the centre there is a bright tent between two consoles with numerous, messy cables, as well as screens, rollers and lamps.

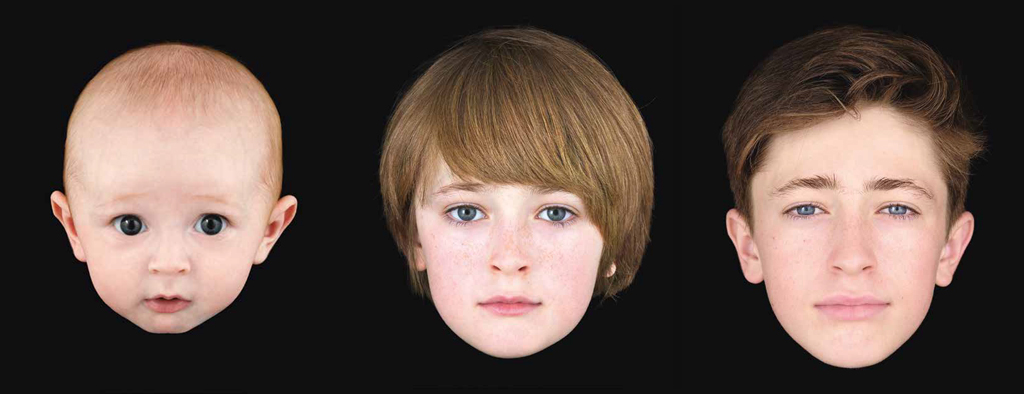

Here, everything is monumental, in the sense that everything is a memory. The face that Antoine Schneck captures, the one he gives to be seen, is at the same time deeply inscribed in the moment when the shooting took place and almost materially in an eternity.

By isolating the object or the face, Antoine Schneck offers a singular relationship to this “thing”: to see it, to perceive it, to feel it as it is alone, out of everything. We then find ourselves detailing the fibre of the fabric of a dress, the grain of a man’s skin, time’s work on a piece of metal. There is such precision in these prints that the usually imperceptible is impossible to not see, not because it’s hidden, but because it is drowned, confused, in a more disturbed entirety. Through an approach that might seem cold, surgical and technical, the photographer manages to reveal the unsuspected intimacy of his subjects, never holding us by the hand, certainly without telling us what to see, let alone trying to show us.

We begin to wonder where this gaze that he offers us comes from, in the physiological sense of the term, what he does to lend us eyes that are not ours, not his, not the same, eyes that know how to see beyond the image. It’s almost surreal, even though it’s hyperreal. From this infinite meticulousness transpires a radical tenderness, which we suspect is the key to this window to the soul.

To find out more about Antoine Schneck’s work, lend

him your face or offer your own :

www.antoineschneck.com

Your singular portraits, on which faces are shown on a black background, just faces, result in large, spectacular prints. How did you get into photography ?

Today, I am a photographer because, from an early age, I was lucky enough to be able to do what I wanted to do. At the age of 12, I found a 24×36 camera at home, far from the only instamatic used to record my family’s birthdays and holidays. There were buttons which puzzled me, so I went to the FNAC and bought myself La photographie en 10 leçons (Photography in 10 lessons). I soon realised that this was a good way to avoid having to write to express myself.

My family let us pursue our passions, but we had to study, and photography schools were rather rare at the time. So it wasn’t until I was about 30 years old that I had the courage to embrace this passion professionally. After studying architecture and cinema, and spending a few years as a cameraman for television, I started working as a photographer for the interior design press. Only then did I develop my career as a portraitist.

I was brought up striving to do the best I could, and I didn’t realise that I was following in the footsteps of my father, a maxillofacial surgeon who spent his life repairing faces as best he could – I had been lucky enough since the age of 14 to be able to occasionally assist him in the operating theatre. I found this face surrounded by blue fields in my portrait work where I define the face with a black veil. After each shot, I rework a lot – rather than “retouch”, I don’t like that term very much. Working on the graphic palette is truly a moment of creation. I don’t make a photo that tries to tell a story, rather one that allows you to look. I am part of this function that photography fulfilled at the end of the 19th century when it freed painting from its function of documenting reality (leading to impressionism in particular). I return to this primary function to enable a relationship between a spectator and a subject, whether they are objects or faces.

Since last spring, the face has been a symbolic danger : the face of the other, if I see it, is my potential contaminant, just as mine is a potential aggressor. Why, in your opinion, does the face wield such power?

Over the last few months, we have become aware of the importance of the face. Levinas has often been quoted on this occasion : the relationship with the other is made through the face one offers. The photographer, however, will spend their time hiding this face, disrupting the reading of this face, covering it with make-up, surrounding it with a setting that wants to catch your eye, telling a story, or even arousing or capturing an emotion by its very presence. My whole job is to try to remove all these disturbances that would prevent direct access to this face. Wearing the mask, this makes us see that the reading of the face, the emotions, was no longer possible and that something was really missing. A face hidden by a mask or, perhaps more discreetly, by make-up, will disturb and hinder the relationship with the other person. The presence of the other, their whole face, forces you to reveal yourself. Watching someone undress through a keyhole is exciting and achievable. Watching someone undressing in the same room as you is something else, it forces you to accept your own intimacy, your relationship with the other. Seeing the face, showing one’s face, this means accepting the presence of the other and thus one’s own vulnerability in the relationship with the other.

How are your shots where the subject, revealing and giving you access to their face, somehow exposes themself naked? Isn’t it too intimate for the subject ?

The people I photograph are in a kind of canvas that prevents them from being seen by others and by me. They find themselves in a cocoon, a belly of light, and feel protected. When I did the portrait of Emmanuel Carrère, after making his face, I suggested that I also do his bust, his bare chest. At the end he explained to me how it had been easier for him to pose shirtless than to pose with his face alone, because he had a defence when he was shirtless. You can’t defend yourself with your face, you can only surrender. In the process of my photographs, there is no stress with the photographer, the person doesn’t see me and this is just the experience I offer to the other person : discovering one’s own face independently of anything else. No one has ever seen their own face. In the morning when we look at ourselves in the middle of the room, we don’t see our face, we see our face looking at the face, which changes according to the moment, the light in that bathroom, our thoughts ; the face, in reality, is a long way behind all that.

What do people who come to be photographed by you, who accept to place themselves in a vulnerable position, look for, apart from the beauty of these flawless portraits ?

They’re not flawless portraits, but it is true that through my work I remove all temporary defects, because the portrait is so precise that anything that would stand out – redness, a badly shaven beard, those marks we all have – would take on too much importance and would hinder access to the face. Subjects are of course looking for a strong artistic experience in addition to discovering their own face.

Are there times when people don’t like what they see when they see themselves in your work ?

This has happened, not frequently, but there have been times when people found it difficult to accept their portrait even though their loved ones liked the image of them. When we do a photo shoot, we take between 5 and 20 photos, then we go to a computer screen and look at them together, and then we choose, always together, the portrait I’m going to work on and shoot. We agree very easily. It’s an important process, because that’s when the person discovers their own face. Often people notice an asymmetry, without knowing that we are all asymmetrical.

I would like to illustrate my point by telling you the story of Valentine Herrenschmidt’s portrait. She has an angioma on her face (a “wine stain”), this young woman was an actress at the time. I had seen her in the theatre, as if through a keyhole, without embarrassment.

After the performance, I plucked up my courage and went to see her backstage. I could hardly look her in the eye, so I told her I would like to make a portrait of her. As I was choosing the photo on the computer screen, I turned to her, her wine stain had disappeared. Her wine stain, which until then had been an external, disruptive element, had returned to her life. When people see this picture, they always say to me, “This woman is so beautiful”; the same person, however, if you saw her in the street, you wouldn’t say to yourself, “She’s so beautiful!” , you wouldn’t dare to look at her. Reintegrating everything that is part of the face and removing any disruptive elements from the relationship with the other, this is my work.

In 2017, you made portraits for Tenou’a of Marceline Loridan-Ivens. Marceline by then could hardly see anything at all. Photographing people who can’t see you because they are physically prevented from doing so, does it make a difference ?

In the end it doesn’t change much in the sense that the important thing is not the gaze that would mark my presence. I don’t want people to see the reflection of my studio in the eye of the subject. On the contrary, I am looking for that neutrality which doesn’t disturb the face. If the person is smiling at me, my presence will be an obstacle to the relationship with the face. When I started doing this work 20 years ago, I went to the Louvre to look at what a painter’s portrait looked like, and I noticed that painters painted a white glow in the upper left corner of the eye. I can’t get this glow when I take a picture because of the translucent booth, so it is redrawn afterwards. My photo doesn’t try to show reality, it creates it, my photo is the creation of one window towards the other.

Interview by Antoine Strobel-Dahan