Lire cet entretien en français / Read this interview in French

Antoine Strobel-Dahan - You chose to exhibit in a former Nazi bunker. How did you find this place, and what first brought you there? And then, what happens — emotionally, politically, and artistically — when Jewish artists take over such a charged and singular space?

Yury Kharchenko - I happened to be at an event in the bunker by accident, and later I got in touch with Marat Guelman. We talked about creating an exhibition — about Jewish identity and about my paintings, which he had seen in my studio. Then I had the idea to approach the bunker because of its Nazi history, and to connect it with the idea of the Gaza tunnels and hostages, as both are underground spaces. The bunker, the history, Berlin — all of it felt deeply connected.

ASD - What influence did the place itself — the bunker — have on the conception and the tone of this project, of this exhibition?

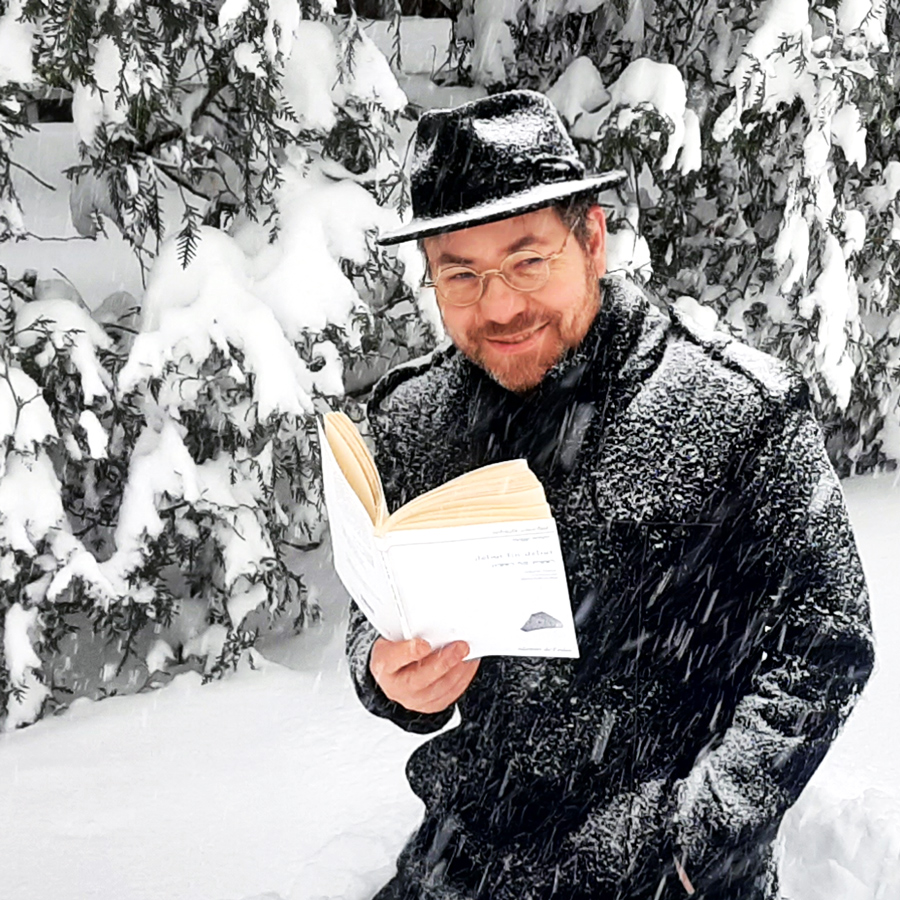

Marat Guelman - What happened with this exhibition is that it’s very strong politically, but also very strong artistically. For us, we’re simply showing very good art works by Jewish artists, while understanding that the political context can sometimes feel like trash. The title is provocative, the place is provocative, and the idea that in Berlin — a city where antisemitism is still present — there’s an exhibition of Jewish artists is provocative as well.

People come in expecting confrontation but find good art instead. That was my idea : to let the context help us show truly strong artistic work. Yes, it takes place in a Nazi bunker — a very heavy space — but inside, there are five delicate artists : two from the United States, two from Germany, and one from Israel. Each speaks in a quiet, often ironic or self‐ironic voice. It’s not a battle. This exhibition is not a battle. But the context makes visitors expect one — and that’s precisely what makes it important.

ASD - Let’s talk about the title — Bad / Good Jews. It’s a fascinating choice. We actually had a long conversation with you, Yury, more than a year ago, and you spoke then about the expectations that the German public and political world have toward Jews — the idea of the “good Jew” who stays in the place assigned to them, as part of what you called “Jew-washing.” So, this “good Jew” fits a political narrative, while the “bad Jew” doesn’t. Is that the idea behind the title? And how do you personally navigate that tension?

MG - It’s not only about political narratives — it’s also about something from our own experience. In Jewish families, it’s quite common to hear someone say, “Oh, this person is Jewish,” and what they mean is, “He’s a very good person — and he’s Jewish.” We’re proud of famous Jews — Einstein, for instance — yes, we’re proud.

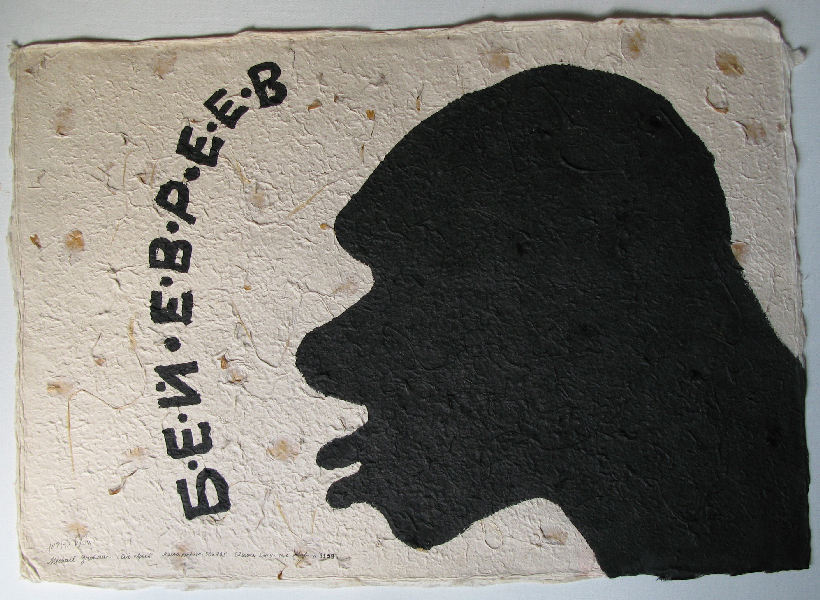

But if we’re proud, and this idea comes from Alexander Melamid’s project (which I completely agree with), then we must also think about the bad Jews too. “Good” and “bad” simply mean that we are like everyone else — Germans, Americans, Russians — we can be good, bad, different. And we’re ready to talk about that openly with the audience. We don’t want to make propaganda for Jews or for Israel ; we want to have an honest conversation, to show that among Jews there are good ones, bad ones, left, right.

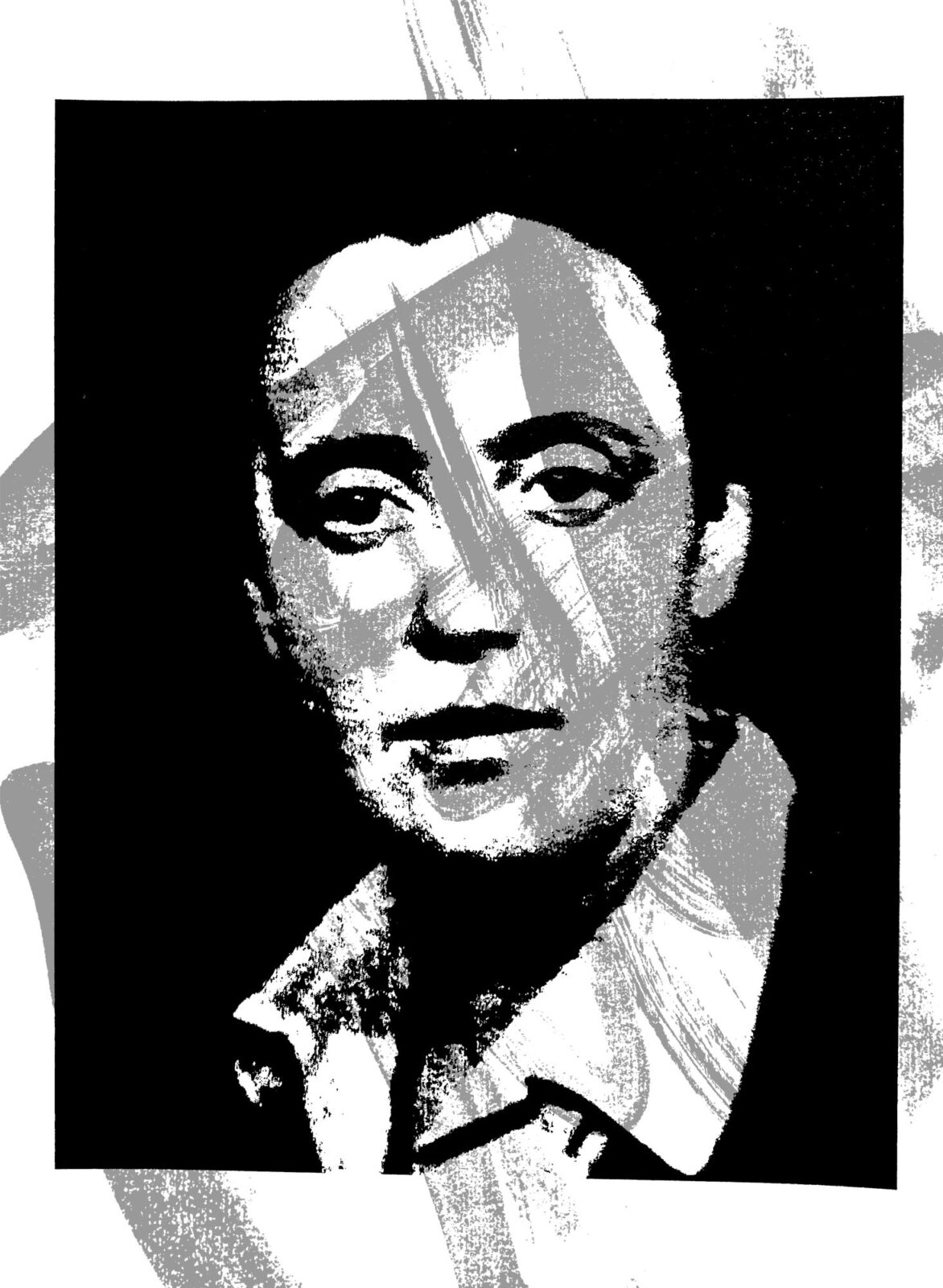

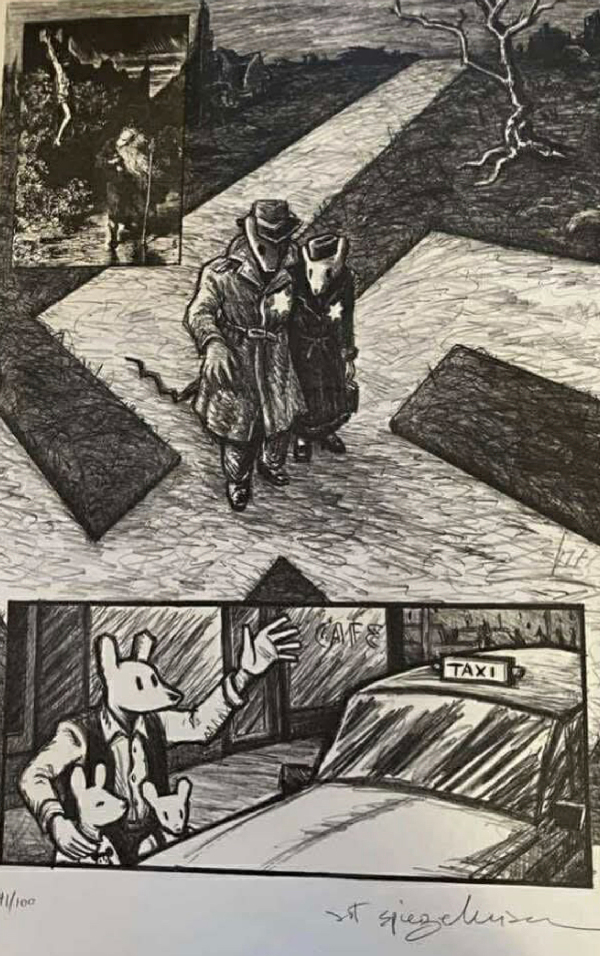

For example, Mikhail Grobman is very pro‐Israel — he’s from Israel, he represents the right wing of Jewish thought. And Art Spiegelman is very much on the left, a true New Yorker. We are all different — good, bad — and, in my opinion, those definitions are meaningless. But it’s a good starting point to have a real discussion about Jews. Maybe, by the end of that discussion, we’ll see how absurd it is to say “good Jew” or “bad Jew,” but as a title, it’s an effective way to begin.

YK – It’s really about opening a broader discussion on Jewish issues. The idea of “bad” and “good” Jews works like a curtain — it draws people in, but once that curtain is lifted, the real conversation begins. It invites people to go deeper. Today, everyone seems obsessed with defining who the “good” Jews and “bad” Jews are — left or right, politically correct or not, American or German — and this constant division has become almost hysterical.

ASD - So, Yury, would you say you’re a good Jew or a bad Jew — as an artist, I mean?

YK - An artist is always on the other side of any political perspective. Before the war in Israel, I was probably closer to the left — except when it came to Israel. The art world is generally very left‐leaning, and many of my friends in Germany are too. But over time, I saw how it turned into ideology, and that reminded me of what we knew in the Soviet Union, where we come from as Russian Jews. So I stepped back from people who started attacking Israel — the ones I call “the bad Jews,” especially in the American art scene. I couldn’t stand that attitude.

What happened on October 7 touched me deeply. It felt personal, and it brought me back to the synagogue after fifteen years of going there only occasionally, just for the holidays. I had studied in a yeshiva long ago, but left after someone told me that art wasn’t Jewish — which I found absurd, especially since the school was founded by Ronald Lauder, one of the biggest art collectors.

After October 7, many Jews, including me, returned to their roots — to the synagogue, to the sense of being one people. For me as an artist, it was an existential awakening : feeling the pain, the connection to Israel, and realizing how many want to see it disappear. That’s how I see it.

By coincidence, Marat Guelman was already friends with German Moyzhes, the CEO of the Ronald S. Lauder community Kahal Adass Jisroel — formerly the yeshiva and Jewish community I had left fifteen years ago — and they have now become one of the supporters of this exhibition project.

ASD - Speaking of this rise in anti-Israel sentiment, anti-Zionism, and antisemitism — which has become terribly strong over the past two years, even if it was already there before — I’m wondering about the ethical responsibility of art. I mean the power of art to provoke, to bring uncomfortable subjects to the table, to force people to engage with things they’d rather ignore or oversimplify. What does that mean for you, Marat, in terms of the irony you sometimes use in your work? And for you, Yury, with the provocation — like your T-Rex in front of the Auschwitz gate, for instance. What would you both say about the ethics of art in facing these challenges — not only as Jewish artists, but also as human beings?

MG - I think the real political statement of this exhibition is simply the fact that it exists — that a group of Jewish artists are showing their work in Berlin, inside a former Nazi bunker. That alone carries a strong message. Because of that, the art itself can be more subtle — full of self‐irony and complexity — and I think that’s the key.

I’ve curated many exhibitions in my life, and I’m convinced it’s a mistake when the political issue and the artistic issue are the same. Here, they’re different. Politically, we say something simple : after October 7, being anti‐Israel and being antisemitic are one and the same. Terror is terror, whatever the ideology behind it.

But inside the exhibition, there’s another layer — the art itself. My work, for instance, is about painting, about difference, about this Jewish instinct to search for something new. There’s self‐irony, and the artists speak in complex, often introspective ways. As artists, we’re probably harsher critics of ourselves than any of our right‐ or left‐wing opponents.

The concept, for me, has two parts : the fact of the exhibition itself, which is already a statement, and the inner world of the artworks. Both matter. And remember — on October 7, in Berlin’s Neukölln district, people were celebrating.

YK – It felt like a part of Berlin had become a department of Hamas. When the massacre of October 7 happened, people were out in the streets, giving out candies and celebrating — celebrating the murder of Jewish people, of babies. It was horrifying to see.

MG - For me, the exhibition itself carries a simple but powerful message — it’s provocative by its very existence. Yet inside, you find something different : self‐irony, strong art, and a real dialogue between the artists. I hope visitors who engage with it will sense the connection between these two layers. That, for me, is what being Jewish means.

I call myself a “bad Jew” — not morally, but because I was born in the Soviet Union. I never really thought about my Jewish identity before coming to Berlin. I was Russian, Moldavian, an enemy of Putin — but being Jewish felt marginal, not central. In Berlin, I realized I was Jewish above all, because I couldn’t be German, and I didn’t want to be Russian. That’s when I began reconnecting with Jewish traditions — and later, after October 7, this identity became truly personal. Those two experiences, Berlin and October 7, made me a real Jew, and my art is a direct response to that transformation.

It’s important for me to show that these two sides — the Jewish boy absorbed in delicate, introspective things, and the Jewish boy who fights in Israel — are the same. One of my paintings shows a Jewish man playing the violin, and the violin becomes a gun.

YK – Marat’s work with the violin that turns into a gun reminded me of The Pianist by Polanski — a musician with no way to defend himself. Today we face a similar problem : Jews who defend themselves are seen as bad Jews, while in Germany the “good Jews” are the dead ones — those remembered in the Stolpersteine, the memorial stones on the streets. You often feel that here as a Jew, you’re viewed only through the Holocaust, not as a living person who thinks, speaks, or stands up for Israel.

That’s why I was so frustrated with many leftist media — they reject the idea of self‐defending Jews, those who serve in the IDF. I painted the IDF logo as a tribute, because my relatives serve there, and others — relatives of my Israeli family members — were killed on October 7. For me, they are heroes, just like my grandfathers, who were Red Army heroes from Stalingrad to Berlin.

ASD - I’d like to ask about heroes. In this exhibition, you bring together very different figures — from Art Spiegelman to Alexander Melamid. Melamid paints Jewish anti-heroes — gangsters, outlaws, ‘bad people,’ not just ‘bad Jews.’ It feels almost like a reverse mirror of Warhol’s idealized portraits. What does that say about Jewish memory — the way it’s built, or sometimes censored? Because, as you were just saying, the definition of a “hero” keeps shifting. For example, Jews were once blamed for not fighting the Nazis, for going “passively” to their deaths, and now, when they do fight to defend themselves, they’re condemned again — as if Jews are only acceptable when they don’t resist. So I wanted to ask about this reversal — about these anti-heroes and what they reveal.

MG - Yes. But it’s very important that Jews can criticize other Jews — that’s something essential to who we are. It’s crucial to show that Jewish people can question and criticize themselves — often more sharply, more honestly, than any antisemite or anti‐Israeli ever could.

YK – I think of people like Masha Gessen, Norman Finkelstein, or Noam Chomsky — and honestly, I don’t know any antisemites who are harsher in their criticism than some of these Jews themselves.

MG - And I think that’s part of our identity — this ability to question ourselves.

ASD - Marat, your career has often combined political and curatorial activism — you’re not exactly known for moderation in that sense. How do you balance this activism with your work as an artist, and with your broader responsibilities — even personal ones, like family — when you’re dealing with all these layers of Jewish trauma? Because that’s essentially what you’re confronting, isn’t it?

MG - You know, I’m from Russia, where they say, “A poet in Russia is more than a poet.” It means that artists have always played an important role in politics and philosophy. My father was a well‐known playwright ; Gorbachev even called him “the father of Perestroika.” After the Soviet collapse, about 60% of Russia’s first parliament came from the arts. So for us, this link between art and politics isn’t unusual.

My own story began with working alongside the most political Russian artists — Ilya Kabakov, Komar and Melamid, Oleg Kulik — all of them deeply engaged. In the 1990s, we dreamed that art could change life ; it was probably naïve, but it felt true then.

When Putin came to power, everything changed. He turned artists into political dissidents by closing Russia off from the world. For him, the golden age was the 19th century — he looks backward, while we, as artists, look forward. We need freedom ; he sees freedom as a Western illusion. That’s why, since around 2012, people like me became enemies of his regime.

I supported the Pussy Riot and Piotr Pavlensky, and in that sense, my story isn’t unique — except maybe that I’ve been more visible. Just a week ago, I was officially named again on a new list — not only a “foreign agent” or “terrorist,” as before, but now one of 23 members of the Antiwar Committee of Russia accused of wanting to seize power. So yes, in their eyes, I’m a very dangerous person.

ASD - Congratulations on your promotion!

MG - Yes, yes, of course — thank you ! I just came back from Brussels, where I met the President of the European Parliament. So now, apparently, they know who to talk to about the future of Russia.

YK – I wasn’t even sure it was a good idea to be associated with Marat Guelman. People warned me, “It’s dangerous — if you say anything against Russia, it’s dangerous for you.” They told me, “I don’t want to deal with you, I don’t want to work with you. If it’s about Israel or about Jewish themes, fine — but don’t say anything against Russia. That’s too risky for us.”

MG - For me, of course, art comes first. My political activism is something I do because I feel I have to — it’s a matter of civic duty. But honestly, it’s not easy to combine the two. As Yury said, some collectors are afraid — maybe they’re thinking about the future. But I’m 65 ; it’s not an age when you try to change who you are. I’m strong enough to be myself and to say, “Okay, you’re afraid — that’s fine.” I’m not the kind of person who expects everyone around me to be a hero. Most people aren’t — 99% of the world isn’t. But for me, this is simply my way.

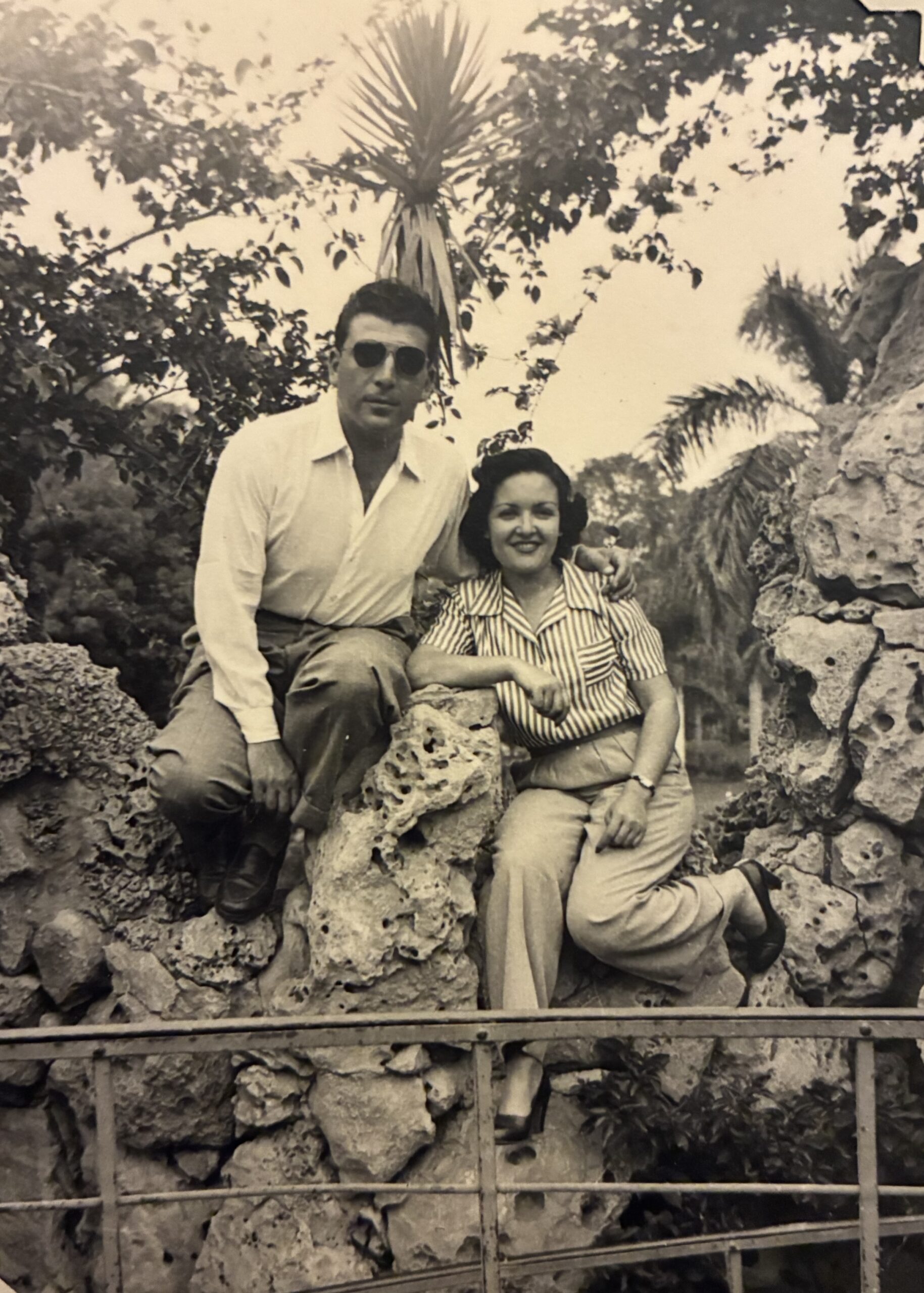

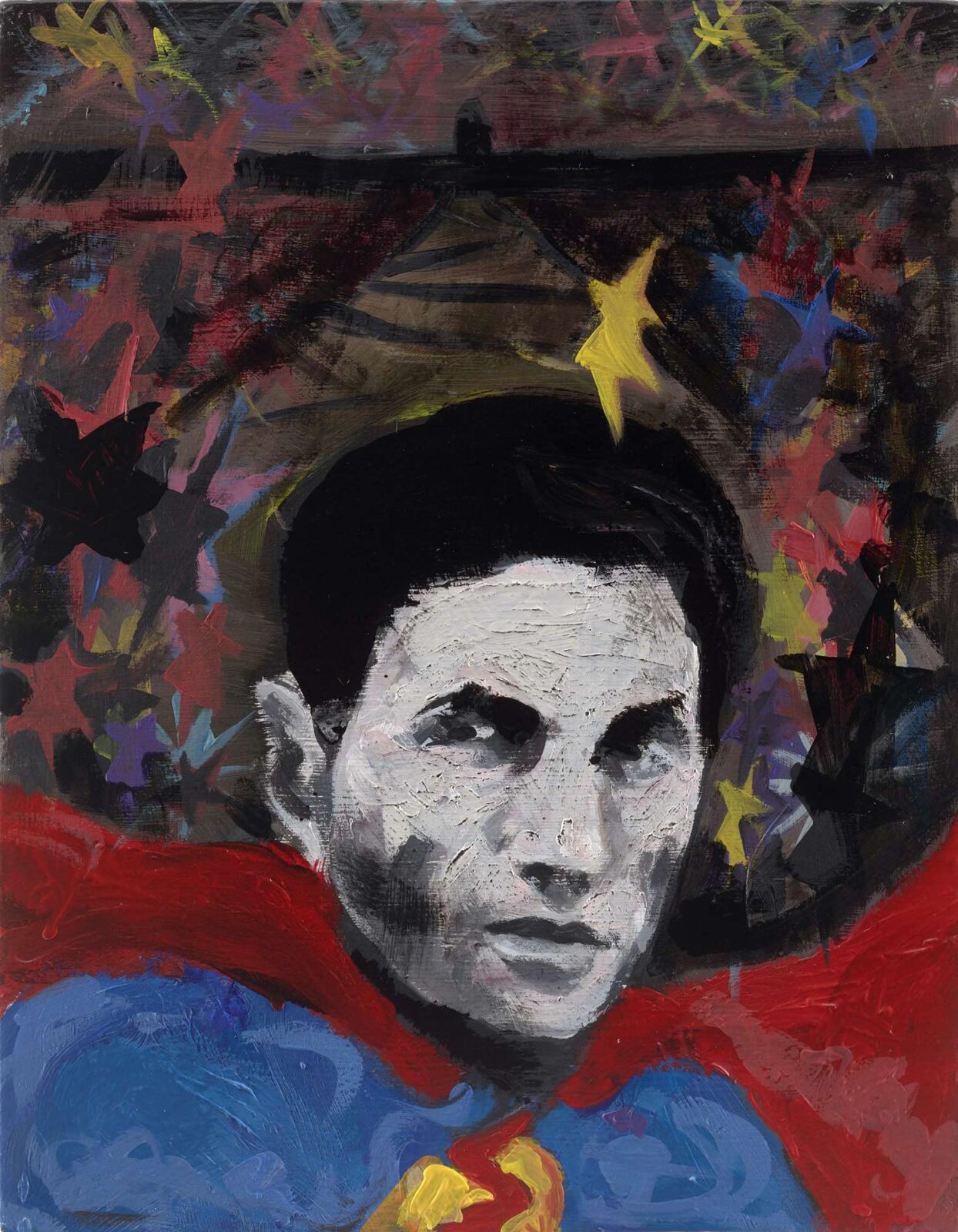

YK – We all know that Superman was created by Jerry Siegel, who was Jewish — and many superheroes like Spider‐Man or Batman are Jewish inventions. That’s why I painted my grandfathers in superhero costumes. They fought from Stalingrad through Warsaw to Berlin, lost their families, and served in the Red Army — it wasn’t an American hero who liberated Auschwitz, it was the Red Army, which included about 800 000 Jews.

With the ongoing war in Ukraine, the red of Superman’s costume took on another meaning for me — the link between the Red Army that fought Hitler and today’s Russia, now fighting a war with no ideology. My grandparents were real heroes, and painting them was my way of opposing this senseless war that divides their legacy. My family suffered on both sides — under the Nazis and in the Gulag — so as Russian Jews living in Germany, we have a kind of vaccine against old Soviet or left‐wing narratives that once painted Israel as a fascist state.

It’s strange to see Europe, especially Germany, support Ukraine while repeating those same clichés about Israel. Germany’s first duty is to protect Jewish lives, yet its major media often portray Israel harshly. When I feel art or politics becoming ideological, it reminds me of Soviet propaganda — and in my art, I want to push back. I use irony to disturb, to make viewers question. Some don’t know whether I’m being pro‐Israel or sarcastic, but that confusion is what opens meaning. Art shouldn’t comfort ; it should provoke and make people think.

ASD - There’s also another exhibition opening at the Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art, on November 20. How did that happen — two shows at the same time, almost 7,000 km apart? Do they connect in any way, or are they completely separate projects?

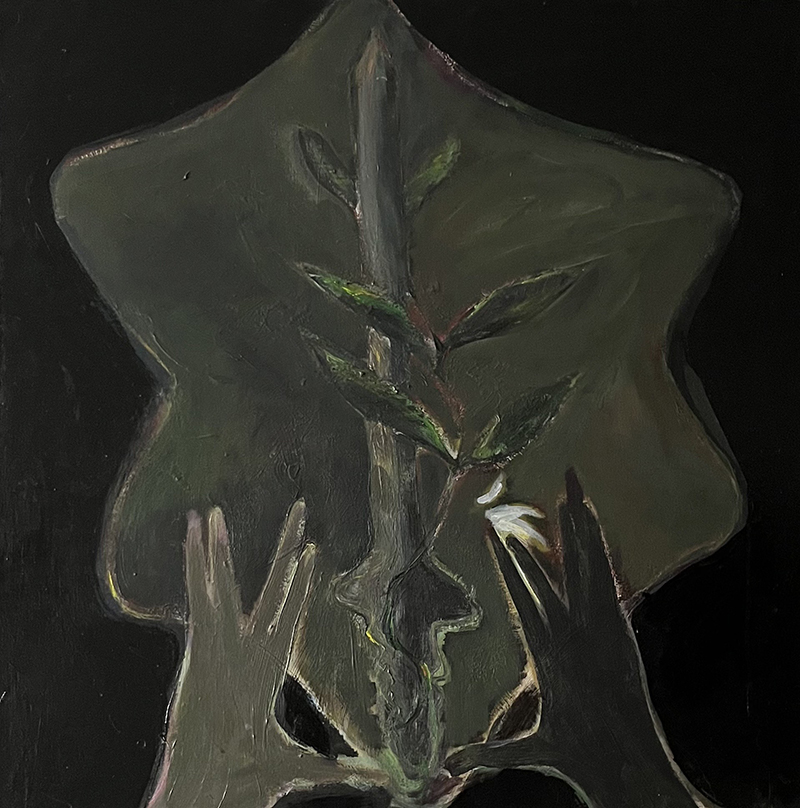

YK – No, no, it just happened as a result of my work over the past three years. I was invited by the artist Joel Silverstein from New Jersey, who is part of the Jewish Art Salon in New York City, the group that organized the show. The piece with the IDF logo and the Kohanim hands — which was featured in the book Tenoua, Oct. 7, In the Shadow of Art in October 2024 — was selected for the Philadelphia exhibition, and honestly, I was embarrassed — I thought, how is that possible ? Who would dare show a work with the IDF logo today, when so many voices are shouting “death to the IDF,” talking about genocide, accusing the Israeli army of atrocities ? I was really surprised they chose it.

That exhibition focuses on art made after October 7 and on the new wave of antisemitism. In a way, the art I created led to this — it opened the door to other exhibitions dealing with these same themes. I never imagined these works would be shown ; I made them simply for myself, for my own soul.

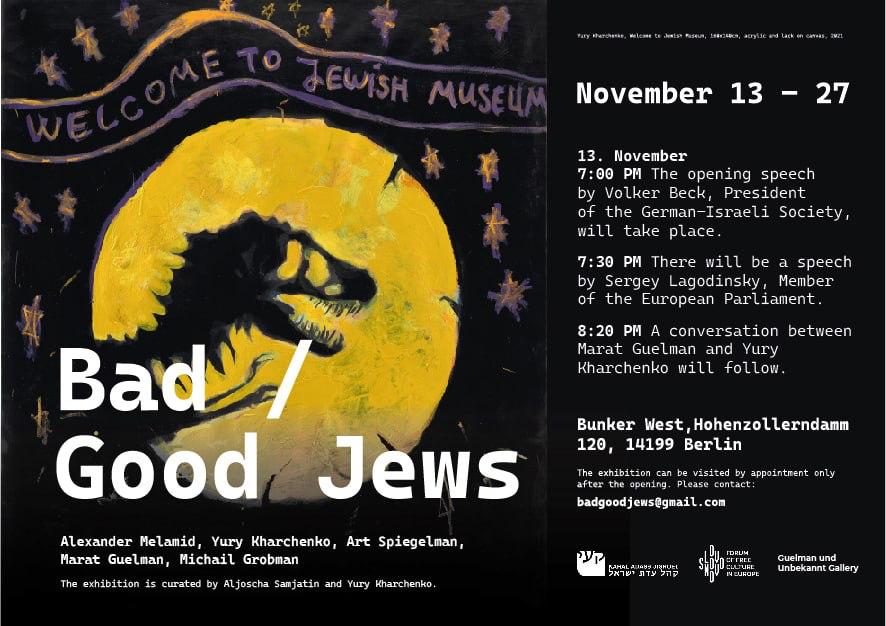

Bad / Good Jews

November 13–27, 2025

Bunker West, Hohenzollerndamm 120, 14199 Berlin

Opening on November 13 at 7pm

With speeches by Volker Beck, President of German‐Israeli Society and Sergey Lagodinsky, Member of the EU Parliament ; and a discussion between Marat Guelman and Yury Kharchenko.

The exhibition can be visited by appointment only after the opening. Please contact : badgoodjews@gmail.com

Fallout: October 7 and the New Antisemitism

November 20, 2025 – March 17, 2026

Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art, 615 N Broad St, Philadelphia

Presented in partnership with Jewish Art Salon NYC

Opening on November 20 at 6pm