This essay was originally published in Hebrew on the online Off-Screen magazine, 12/1/23.

A French version of this essay is to be released by early October on Tenoua’s website.

Cet essai a été publié à l’origine en hébreu dans le magazine en ligne "Off-Screen" le 1er décembre 2023.

Une version française de cet essai sera publiée début octobre sur le site de Tenoua.

המאמר הזה פורסם במקור בעברית במגזין המקוון "אוף סקרין" ב‑1 בדצמבר 2023.

גרסה צרפתית של המאמר צפויה להתפרסם בתחילת אוקטובר באתר של תנואה.

Sprawling fields at dawn, bordered by the Gaza Strip, serve as the opening shot of The Boy, a short film by the late Yahav Winner, currently being shown in Israeli cinemas. The morning chorus—whispering winds, the chirping of birds, the gentle rustling of wheat fields—precedes even the logos of the supporting film funds. From the outset, Winner insists that we acknowledge Israel’s Gaza Envelope region, which remained largely out of sight and mind for most Israelis during the film’s production in early 2023. This deliberate choice underscores a profound gap inherent in Israeli cinema since its beginning : the conspicuous absence of peripheral regions and towns, like Kibbutz Kfar Aza depicted in this film, or Kiryat Shmona and Shlomi in northern Israel (Arab, Bedouin, and Druze towns are altogether nonexistent in the Israeli cinematic landscape.) I challenge you to recall when you last watched a film set in such a location.

The field is shrouded in an ominous early morning mist. The calls of the muezzin echo from the numerous mosques dotting the crowded landscape of Gaza. On the left side of the frame, a gentle stream of water erupts from the field, gradually intensifying and rising higher, eventually obscuring some of the distant houses in Gaza. The sound of the rush of water blends with the wind’s whispers and the multitude of calls to prayer. A distant rumble heralds the arrival of a military vehicle as it makes its way along the access road into the Gaza Strip. Meanwhile, the towering column of water, later revealed to be an exploded irrigation faucet, continues to steadily ascend. The sounds preceding each image evoke a feeling of delayed dissonance. Rotem Dror’s meticulous sound design serves as a precursor to the unfolding narrative, prompting viewers to contemplate the meaning behind each sound. Later in the film, the ambiguity of these sounds leaves viewers questioning whether they originate from a Palestinian rocket launch or Israeli military activity. This poignant cinematic decision serves to depict a context that remains unseen by the Israeli viewer, despite the Gaza Strip being nearby and visible.

This opening sequence strikingly captures the intricate complexity of the Negev region known as the Gaza Envelope. Feelings of lost control and helplessness are subdued and overwhelmed by the region’s deceptive natural beauty, creating a reality where the only stable element is the constant state of instability. The ruptured water pipe juxtaposed with the solitary military jeep serves as a stark reminder of humanity’s insignificance in the face of the perpetual turmoil that defines « the situation, » as Israelis often refer to the Israel‐Palestine conflict. The vast, open long shot immerses the viewer in the space, yet the menacing sounds of nature and the Gaza Strip intertwine, echoing the enduring trauma and sorrow concealed within the captivating yet haunting landscape. Consequently, the shot remains closed off and foreboding, withholding full comprehension of the landscape due to the intricate complexities it embodies, leaving much unsaid and unexplained.

Therefore, long before the sequence and the film can be deemed prophetic—a descriptor I deem simultaneously warranted, unsettling, and infuriating as a resident of Be’eri who experienced the events of October 7 firsthand—they should be primarily recognized as an artistic portrayal of the intolerable daily existence spanning over two decades in the region. In less than three minutes, Winner skillfully encapsulated this paradoxical reality by illuminating the absurd circumstances of life in the Gaza Envelope.

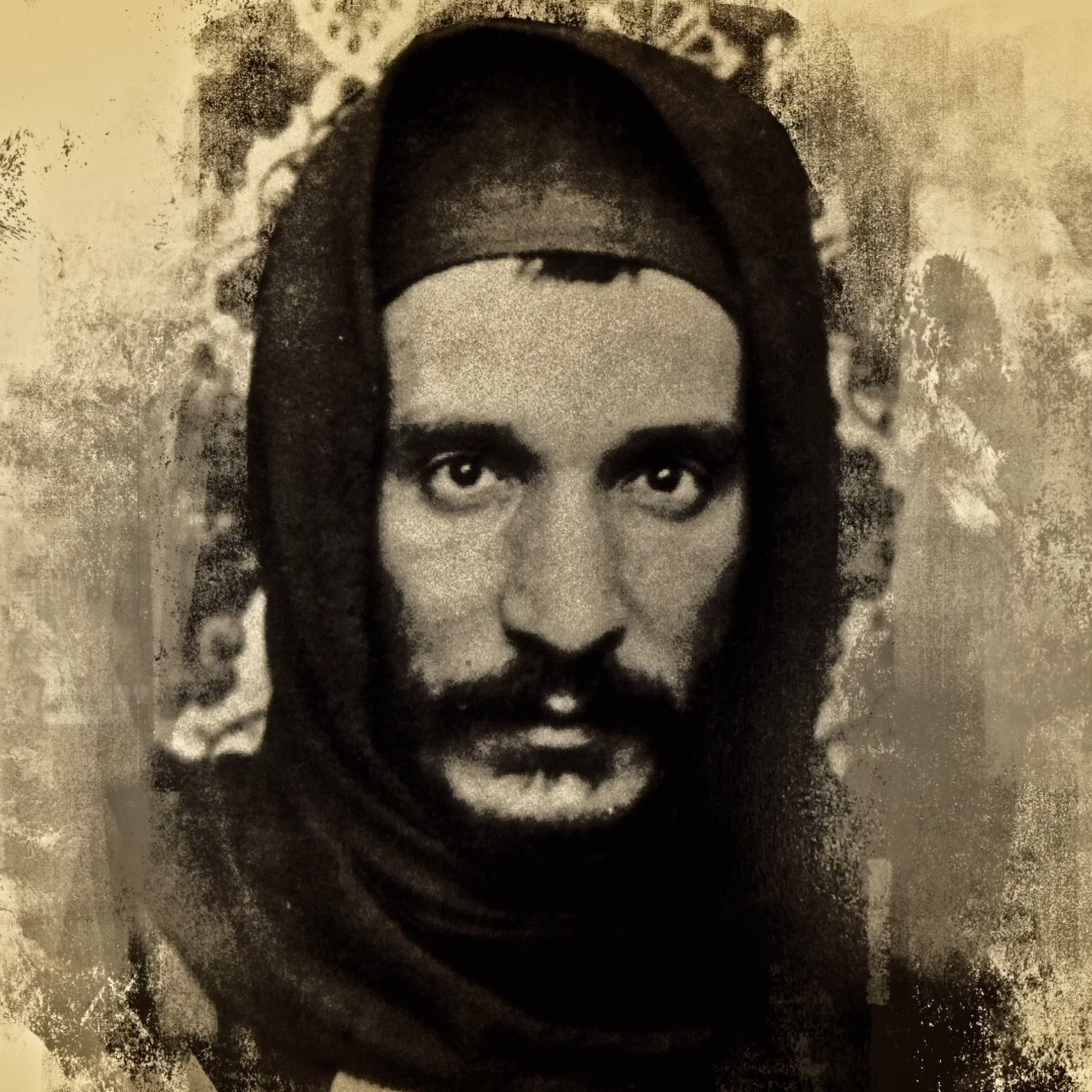

The potential of The Boy’s opening sequence—arguably one of the most remarkable in Israeli cinema, particularly in recent years—transcends the confines of Winner’s impressive film. Winner was murdered on that fateful Saturday while protecting his wife, Shailee (herself a filmmaker and the editor of the film), and their one‐month‐old daughter, Shaya. Understandably, current discussions predominantly revolve around the film’s tragic symbolism and Winner’s immense potential, which was brutally cut short. The active involvement of Kfar Aza and its residents in the film, along with the knowledge that many of those portrayed were either murdered or taken hostage, unintentionally transforms it into a monument of memory and unresolved trauma. It is unlikely that any of us who experienced this trauma will ever fully come to terms with it.

These aspects are accompanied by numerous other concerns, many of which are related to cinema’s fundamental inquiries and its connection to memory and reality. This prompts a reexamination of Andre Bazan’s theory, which laid the groundwork for modernist discourse on the essence of cinema. Such contemplation must not be reduced to the film’s tragic symbolism. Drawing from Bazin, the impending danger is preserving the current moment and context in a manner that confines the discourse solely to the symbolic level. Instead, The Boy could serve as a kind of prelude, introducing a new aesthetic in Israeli cinema that aspires, perhaps for the very first time, to use new tools to articulate the intangible, or put differently, the inadequacy of oral and written language to fully capture the magnitude of the horrors of October 7.

The unprecedented events that struck Israel, coupled with a year marked by heightened incitement, division, and a government attempting to establish authoritarian rule, demand a cinematic response that surpasses anything previously attempted in the annals of Israeli cinema. This response must draw from the deepest inner wounds and exposed nerves of the present time and place. The reality we are facing has long transcended the bounds of sanity—a term that appears to have lost all relevance in Israel over the past year—and thus demands an appropriate form and aesthetic. From the earliest frames of The Boy, Winner demonstrated that he was deftly aware of this. Tragically, his horrific murder disrupted what could have been a continued exploration of this meaningful and pertinent creative pursuit.

Between the local and the universal

Israeli cinema has historically exhibited a significant delay in responding to the major national catastrophes that have afflicted the country since its establishment. It was not until almost three decades after the 1973 War that Amos Gitai released his film Kippur, marking a bold and direct first cinematic attempt to confront the scale of the horrors and chaos of that battlefield and the challenge of representing it. Similarly, over two decades passed before the First Lebanon War and the occupation of southern Lebanon were significantly depicted on screen, as Yosef Sider’s Beaufort, Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir, and Shmuel Maoz’s Lebanon were released within the span of three years. Few narrative films produced in the immediate aftermath of these wars attempted to explore their events or consequences. Most of these focused on the shellshock experienced by returning combatants, aiming to understand their struggles and contribute to broader national healing. Among these films, Waltz with Bashir stands out for effectively grappling with the recollection of trauma and its associated dangers. Similar challenges are encountered in attempts to portray the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Even Yaron Zilberman’s Incitement, while taking the bold step of centering the film on the assassin Yigal Amir, oversimplified the issue into a narrative of purely sectarian tension.

I regret to report a significant challenge facing Israeli cinema. Broadly speaking, and while recognizing that there are exceptions, it is evident that over the past two decades, and especially in recent years, Israeli cinema has avoided engaging with the harsh realities of Israeli existence and the nuanced complexities that define life here. Let it be stated from the outset : political narrative cinema does exist to some extent in Israel. Kolirin’s films are a prominent example, eloquently and purposefully portraying the tension between the universal and the local. Other examples from the past decade include Shmuel Maoz’s Foxtrot, Yuval Adler’s Bethlehem, and Yariv Horowitz’s Rock the Casbah (though I find them weaker films). Still, overall, the narrative construction and especially the aesthetics of Israeli cinema clearly tend towards the universal.

This would not have been a problem if the universal elements were rooted in the local context, in both the beautiful and disturbing particularities that define the Israeli experience. Yet, until now, there has been a glaring absence of iconography exploring many of Israel’s social and geographical spaces, most of which have rarely been portrayed in film. Furthermore, the stability of universally understood concepts such as « space » and « place » has been upended by the unprecedented massacre of October 7 : it has become clear that every city and town in Israel faces the imminent threat of complete annihilation, with the potential for the most heinous atrocities humanity can commit. It is, therefore, imperative to establish distinct, local interpretations for these terms to imbue existing cinematic paradigms with the uniqueness of Israeli existence.

The inclination towards universality, which obscures and oversimplifies the Israeli experience, has plagued Israeli cinema for the past thirty years. This tendency can be traced back to the films of the New Sensibility movement, which is commonly understood to have begun in 1967. Even before, Uri Zohar’s 1964 film A Hole in the Moon, a precursor to the New Sensibility movement and cornerstone of avant‐garde Israeli cinema, represented an aesthetic struggle to depart from propagandistic heroic‐nationalist cinema in the years following the state’s establishment. It is worth noting that the New Sensibility movement is unquestionably the most significant cinematic movement in the brief history of local film production. The aesthetic and thematic paradigm shift it instigated propelled Israeli cinema beyond propagandistic stagnation, guiding it and Israeli culture as a whole into uncharted artistic realms.

The New Sensibility movement represented a breath of fresh air, demonstrating that art could be created for its own sake and to realize an individual creative vision. This perspective sharply differed from the prevailing atmosphere of social conformity evident in much of Israeli artwork until 1967, and even more so amid the heightened messianic fervor that emerged following Israel’s victory in the 1967 War. The films produced by the group expressed a rejection of the state, the Zionist ideology, and nationalist sentiments in favor of absolute individual autonomy. This also marked the beginning of the understandable yet perilous isolationism among Israel’s secular population. David Perlov’s Diary stands out as an exception, skillfully addressing this issue with remarkable complexity. Additionally, Uri Zohar’s Big Eyes and Avraham Hefner’s Where is Daniel Wax?, among the finest New Sensibility films, pioneeringly recognized that the self‐imposed internal siege experienced by the male protagonists symbolized a collective loss of direction, leading to moral and spiritual self‐destruction from which escape may be impossible.

The convenient tendency to rely on universal themes is best exemplified by the family film genre, which has dominated contemporary Israeli cinema in recent decades. The frequent focus on the family unit can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the family holds a central place in Israeli culture and society. Secondly, the tension between the personal and national creates an urge to prioritize individual autonomy over collective identity. Familial relationships seem to offer an ideal framework for Israeli cinema – the multicultural compositions of Israeli families serve as a microcosm of the country’s diverse population, while also offering distinct and deeply personal stories. This dynamic confines the family theme to a dangerous and numbing equilibrium, employed as a panacea to depict the Israeli experience while also engaging with the world and appealing for understanding and acceptance. Films like the Viviane Amsalem Trilogy and Nir Bergman’s Broken Wings stand out favorably within this genre (though they are not the only ones). And although they possess distinct universal and festival‐friendly qualities, the context and timing of their creation reflect broader and unique Israeli preoccupations. It would be difficult to imagine them being produced elsewhere, certainly not with the same sense of urgency.

For a brief moment in time, Israeli cinema appeared to be undergoing a much‐welcomed and unexpected transformation, only to be cut short before reaching its complete potential. In her influential 2014 article published in the Ha’aretz daily, writer Neta Alexander highlighted a cluster of contemporary Israeli films that she dubbed the New Violence movement. While avoiding direct confrontation with the Israeli‐Palestinian conflict, these films nevertheless expressed the underlying violence persistently surfacing within Israeli society and spaces. As Alexander observed, « New Movement filmmakers express the constant tension between their Israeli identity and their desire to situate themselves within a globalized sphere. » Yet I argue that these filmmakers have crafted characters who avoid direct political engagement and produced atemporal films that rely on universal aesthetics as a means to confront the profound violence ingrained within Israeli society, particularly on a social level. The films associated with the New Violence movement, such as Keren Yedaya’s That Lovely Girl, Tom Shoval’s Youth, Idan Hubel’s The Cutoff Man, and Johnathan Gurfinkel’s Six Acts, all challenged the tendency towards universality through their cinematic forms, albeit perhaps unconsciously. However, the promising wave of New Violence films was abruptly yet understandably cut short. For most of these filmmakers, these films marked their first full‐length feature production. The well‐known difficulties in securing financing for film projects in Israel, along with the conservative nature of the Israeli film funds, likely prevented many of them from further cultivating the promising style they had started to establish.

Instead, it appears that there is an increasing tendency to portray individual experiences as the only factor shaping local reality. It would be absurd and unnecessary to dispute the assertion that « the personal is political, » yet it seems this viewpoint has overly dominated local filmmaking. This assertion is not meant to lessen the significance of numerous films of this kind ; rather, it provides further evidence of the complexities that continue to burden the New Sensibility movement. The concept of « the personal is political » has transformed into a limiting idea within Israeli narrative and documentary cinema. It functions as a convenient trap through which filmmakers excessively emphasize the nearly non‐existent boundaries between the private and national domains. Personal documentaries have still managed, to some extent, to explore the intriguing complexity surrounding these issues, as they turn the camera inward and attempt to grapple with the repercussions of both personal and national ancestral transgressions (as argued by Shmuel Duvdevani in his book First Person Camera). However, the inclination towards excessive personalization—and towards excessive universality—is most notably demonstrated in recent years by the films of Hadas Ben‐Aroya. (It is important to note that I do not doubt Ben‐Aroya’s considerable talent ; nevertheless, it is fair to acknowledge that my appreciation for her filmmaking diminishes with each successive work.)

While it is true that The Boy’s narrative choices lean towards the universal and simplistic in terms of its aesthetics, plot, and direction, it also benefits from the succinctness of the short film format. Winner favors the haunted, traumatized, and grief‐stricken interiority of the protagonist, expressing it in every scene, camera movement, and through the impressive sound design. For example, the agonized son’s desire to watch foreign media news reports about events occurring just a few kilometers beyond the border is thwarted by the family’s preference to watch a local TV reality show. This serves as another charged and effective expression of the collective desire to suppress the son’s anticipated emotional outburst in subsequent scenes.

Yet simultaneously, The Boy intelligently draws its universal elements from the local moment and unique events experienced by the Israeli towns surrounding Gaza. Unlike many father‐son films that have flooded Israeli cinema in the past two decades, in this instance, the father character does not symbolize a generational disconnect or a broken masculinity. Instead, he embodies something much more intricate – the inability to confront the verbal breakdown at the heart of his son’s recurring trauma. In this regard, Winner’s film continues a compelling thematic trajectory seen in recent years, exemplified by films such as Oren Gerner’s Africa, Omri Dekel-Kadosh’s The Accident, and Dani Rosenberg’s The Death of Cinema and My Father Too. What binds these films together is their efforts to address the absence of the father figure in twenty‐first‐century Israeli cinema. The Boy represents the most recent contribution to this undertaking.

The tectonic rift with the global film and art community offers additional impetus for initiating such creative exploration. At best, this rift stems from blatant neglect to address the current events, as evidenced by the absence of any statements on the matter from most major festivals. At its worst, it demonstrates an unfortunate ignorance, as seen in events such as the IDFA Festival and the reception of the Israeli television series Chanshi at the Stockholm Festival, along with the emergence of numerous filmmakers and actors who have suddenly discovered their political voice and appear to possess a thorough understanding of Middle Eastern affairs. Over the past two decades, too many films produced in Israel seem to be striving excessively to appeal to international festivals – another manifestation of the generic universalism that dominates Israeli cinema. However, it is worth noting that Israel is not alone in facing this issue. As previously discussed, The Boy also falls into this trap at various points throughout the film. Nonetheless, the underlying struggles that drive its production and shape the protagonist’s perspective, along with his unspoken, simmering trauma, are undeniable. By crafting the boy’s character and attempting to unravel and break the siege of traumatic silence confining him, the unique nature of his struggle undergoes a beautiful and original transformation into a universal experience.

Toward an intangible cinema

The Intangible Cinema movement will face two primary and complex challenges. The first significant challenge is the overwhelming barbarism and malevolence that characterized the Hamas‐led assault on Israeli soil. Having directly experienced the assault—not having witnessed the murders firsthand but facing its aftermath, including the sight of corpses and massive destruction—I struggle to reconcile my own survival with the knowledge that just meters away, entire families were burned alive and erased, while civilians were murdered and raped to an extent indicating genocidal intent. Many of my friends and relatives have expressed similar sentiments in the kibbutz.

The aesthetics of Intangible Cinema must navigate the dissonance of this extremity with sensitivity, especially in films aiming to depict scenes from the massacre or reenact its horrors. These works must avoid descending into pornographic or didactic portrayals of evil and horror or veering into superficial or clichéd political statements. This caution is warranted because if evil indeed exists in such dimensions and forms, any semblance of temporality and ideology becomes irrelevant, even if they are intrinsic to the atrocities. The moment when such cruel acts are committed nullifies any prior forms of human measurement and definition. This is not because these forces of evil are supernatural or transcendent, but because they epitomize humanity at its lowest and underscore the failure of any ideology seeking to justify it.

The representational challenge posed by the October 7 massacre is unprecedented in modern history, given the systematic video documentation and snuff videos recorded by Hamas‐led militants. It seems the massacre in the Israeli towns surrounding Gaza is the first organized terror attack in history to be meticulously chronicled from start to finish by the perpetrators, victims, and survivors alike. In addition, live television broadcasts aired reporters documenting the real‐time escape of survivors from the Nova rave attack. The accelerated technological changes in the 23 years since the September 11 attacks have allowed every individual to produce their own personal Rashomon, contributing to the broader narrative of the unfolding events.

Moreover, the intertwining surplus of horrific videos exacerbates the excess of horror. Readily available for viewing at any moment, these videos diminish and inadvertently trivialize the intangible threat in an effort to render it tangible, understandable, and accessible. However, this effort is inherently futile, as it frames the horrors within an endless cycle of brutality, focusing solely on the violent acts and reducing them to their brutal violence. Intangible Cinema will be forced to confront this by crafting contrasting imagery that can delve deeper and offer a more fitting response than this expected tendency toward simplification. The fragmented and truncated nature of these horrific videos is a testament to the privatization of individual experiences in an age of instant documentation. Above all, it underscores the profound sense of abandonment amid an escalating catastrophe of monumental proportions.

The second challenge arises from the profound silence and muteness of such atrocities. The volumes of text that have been written and will continue to be written, as well as the vast array of visual imagery that has been and will continue to be produced, must grapple with the recognition that sometimes the most appropriate response to atrocities is to surrender to the silence ; to the immense void left by the moments of cruelty and dehumanization. Many works will seek to depict the events of October 7, whether through sweeping epics aiming for comprehensive recreation or more intimate portrayals focusing on the remarkable tales of heroism and survival. All such films will inevitably confront these challenges, prompting the question of who will yield to the temptation of creating an Israeli Schindler's List (Spoiler alert : there will likely be more than one.)

There are several potential solutions to this paradox.

First, the core principle guiding Intangible Cinema narratives should be the obsoleteness of the exposition in its conventional form. The notable uniqueness of The Boy’s opening sequence stems from Weiner’s understanding that when tackling such complex realities, whether they unfold in an objective realm or within wholly fictional contexts, they are inherent and predate the film’s starting point, regardless of the camera’s role of representing the viewers” gaze. Despite its apparent simplicity, this understanding appears absent from most Israeli films.

Therefore, recognizing the abundance of filmmakers with significantly more imaginative minds than my own, I will focus on what might appear to be a more « conservative » approach : genre films, which, except for comedy, are desperately lacking in Israeli cinema. The aesthetics of Intangible Cinema could be cultivated by revisiting established genres. At the heart of all classical genres (and frequently their derivative subgenres) lie fundamental and existential human quandaries, explored through various perspectives and conventions. This could also facilitate an examination of the destabilized concepts of « space » and « place » since October 7.

Relying on genres may appear to be an entirely universalist approach, given the deeply entrenched conventions tied to them. Yet this steadfast conservatism (even postmodern works attempting to subvert genre conventions often do so predictably and mechanically) can emphasize the ongoing existential threat of local life. Consequently, the threat can effectively be eroded, undermined, and redefined (a specific example from an older Israeli film will be provided later to illustrate this point).

The absence of horror films, for example, underscores the gap still facing Israeli cinema and culture in addressing the conscious and subconscious specters haunting this land. In countries that effectively confront the ghosts of their past and present, many horror films seem to be produced. The absence of Israeli horror films appears to be more rooted in local disdain for this genre and its perceived inferiority rather than surface‐level pseudo‐psychological explanations such as, « The country’s reality is already too violent—who needs such films anyway ? » Utilizing the conventions of horror films to confront the atrocities of October 7 seems warranted. At first glance, this might appear contradictory to the earlier discussion on the pornography of evil, yet the opposite is true. There are methods to depict extreme violence in all its cruelty and brutality without resorting to an artificiality that strips away its essence and temporality. From within the heart of darkness of the horror genre, which seeks to impose order on the chaos of human brutality, several brutal truths to articulate through alternative methods can be unearthed. Most importantly, horror films have the potential to tap into the specific historical fears of Jews that were brought to the surface by this attack.

That being said, I believe there is also a need for a reevaluation and reinterpretation of another genre : the heroic‐nationalist propaganda film. It is easy to critique, diminish, and even suppress the early stages of Israeli cinema due to its overwhelming patriotism and Zionism. However, these films played a significant aesthetic role in shaping Israel’s emerging visual identity. Israel’s national‐heroic cinema focused on canonizing collective Zionist myths while violently ignoring the existence of Arab residents (and later on, non‐Ashkenazi Jews.) Nevertheless, some of these films possess additional complexities and layers that can be harnessed in Intangible Cinema. Baruch Dienar’s They Were Ten (1960) stands out as the most significant among them. Its unique utilization of the Western film genre, with its values and ideology, imbues it with unexpected ideological ambivalence, especially from a distance of sixty years. Casually mislabeling it as nationalistic‐heroic cinema was a mistake that confined it to a narrow and stifling category. Through its propagandistic aesthetics and clichéd dialogue about immigration and land conquest, Dienar shed light—for the first time in Israeli cinema—on the severe and even self‐destructive consequences of Zionism’s realization.

In contrast to classic Westerns, where camera angles, composition, and editing magnify and glorify the land awaiting redemption, Dienar highlights the perpetual existential dangers lurking in the land. The land and space are destabilized to the point of stubborn impenetrability to the ten idealistic settlers. However, the most audacious narrative twist occurs towards the film’s end. When a young horse thief from a neighboring Arab village is caught red‐handed, the group decides to hold him captive until the stolen horse is returned. The following day, they prepare for a confrontation with the villagers, but the conflict never materializes and the young thief is ultimately released. Subsequently, when Yosef, the group’s leader, buries his weapon in the ground, it is revealed that his wife, who had recently given birth to their only daughter, succumbed to fever. Yosef’s decision to escalate the situation through violence, despite amicable relations with the village head, indirectly results in his first and most personal sacrifice. By resorting to violence in service of ideological objectives, Yosef sacrifices his wife.

The final scene of the film depicts Mania’s funeral. The camera’s low angle and the mountain on which the funeral occurs obstruct the full view of the space. As the camera slowly ascends, we follow Yosef from afar as he walks away from the freshly dug grave. The spatial perspective remains unchanged, conveying a sense of unease and threat, prompting contemplation on the broader objectives of Zionism. Rainfall accompanies the scene, symbolizing hope as the drought ends, while the changing season signifies renewal. Nevertheless, the recitation of the Kaddish prayer over Mania’s grave and Yosef’s solitary walk towards the modest brick house where the group resides evoke additional doubts and questions about the cost already paid and the potential future sacrifices for the redemption of the land and the Zionist cause. Apart from the optimism imparted to the viewer, the conclusion of the film stands as one of the earliest instances in Israeli cinema to highlight the inherent fractures and human toll of the Zionist project.

Dienar’s choice to anchor his film in genre conventions and formalism, while intricately adapting them to local contexts through the spatial design, evokes an ideological ambivalence recognized by nearly every Israeli‐Jewish viewer. Whether intentionally or not, Dienar liberates his film from complete conformity to a fundamentally conservative genre. In doing so, he subverts the traditions of nationalist‐heroic cinema and ultimately brings it to its conclusion.

Viewing the opening sequence of The Boy, I could not help but be reminded of They Were Ten’s final scene. While Dienar’s concluding scene marked the end of a propagandistic cinema unconditionally mobilized in defense of Israel, Winner’s opening sequence is saturated with heartbreak, love, and profound rage towards this place and the brutal toll it continues to exact. Amid the current polarization, there is a critical need to return to filmmaking that directly addresses national concerns, but this time, without falling into the trap of propaganda. The Boy highlights one of the numerous failures of the state to safeguard its citizens, leaving them to fend for themselves amidst enemy assaults. From a moral and ideological perspective, Intangible Cinema must harness novel or previously unexplored aesthetic means to depict the collapse of one of the foundational pillars of the state. To begin this exploration, the true harsh realities of life in this land must be emphasized, including both its violent brutality and its considerable beauty. There are countless cinematic approaches, many of which are far more original than what I have suggested here.

Unlike previous traumas in Israel’s past, we cannot afford to delay our response by twenty, ten, or even five years this time—the cinematic reaction must be immediate. Addressing the events of October 7 will require grappling with the intangible dimensions of the trauma and exploring how it can be portrayed, all while tapping into the profound and recent pain it caused.

Translated by : Daniel Bernstein