Lire cet article en français / Read this article in French

Ma nishtanah ha-laylah hazeh mikol ha-leylot… מה נשתנה הלילה הזה מכל הלילות

I know what you’re thinking : the rabbi isn’t doing well. She’s mixing things up, she must have thought it was the night of Passover instead of Rosh HaShana, and she chose the wrong song.

Well, no : these are precisely the words I want to say tonight. I know full well they were written for another night, for the Seder and for the “Four Questions” asked by children on Passover night…

And yet, it seems to me they were written for today and for right now—for this year and for this evening—for everything we are about to experience together.

Ma nishtanah ha-laylah hazeh mikol ha-leylot… מה נשתנה הלילה הזה מכל הלילות

How is this night different from all other nights ?

Or rather : how are these yamim nora’im, these “Days of Awe,” unlike any others ? It is eerily dark. And in this darkness, many of us feel the urge to ask other questions—not the four traditional ones of Passover, but many other questions that haunt us…

– Why have we come to this point ?

– Why, in the face of both religious and international events, do we live this strange simultaneity of liturgical calendars and diplomatic agendas ?

– Why are we continually caught in a vise, between extremes ? Invited to defend or justify ourselves, no matter what our positions may be about events taking place thousands of kilometers from here ?

– Why, according to a surreal poll published on September 19, do so many of our fellow citizens consider it “legitimate to target French Jews in the name of the conflict in Gaza” — that is, for the politics of a country of which most are not even citizens ?

– Why is this festival where we eat apples and honey, to celebrate the wholeness of the world and its sweetness… ha-laylah hazeh, ha-laylah hazeh, maror, this night we eat bitter herbs… why is this festival so steeped in bitterness this year, and why is it accompanied by a sense of failure and apprehension about the future ?

– Why are we, again and again, afraid for our children ?

– Why has it become so difficult to speak to one another ? To engage in dialogue with the world around us, or to talk among ourselves ? Why is there so much silence, or on the contrary so much shouting and violent conflict in our lives — in our workplaces, in our universities, on social media, and even in our communities and within our families ?

– Why, ha-laylah hazeh kulanu mesubim — הלילה הזה כולנו מסובים — this year are we all prostrated and, in a certain way, slumped, wondering where these times are leading us ?

And I could go on, enumerating endless questions, all of which will remain unanswered.

This week, as the High Holidays approached, I received many messages from members of our community. Most of them were New Year wishes. But I was struck to see that, at times, congregants of the synagogue were asking me for something — or precisely the opposite.

Some wrote to me : “Rabbi, I hope you will not speak about politics in your sermons. I couldn’t stand it.”

And others wrote : “Rabbi, I hope you will not avoid speaking about it. If you remain silent, I couldn’t stand it.”

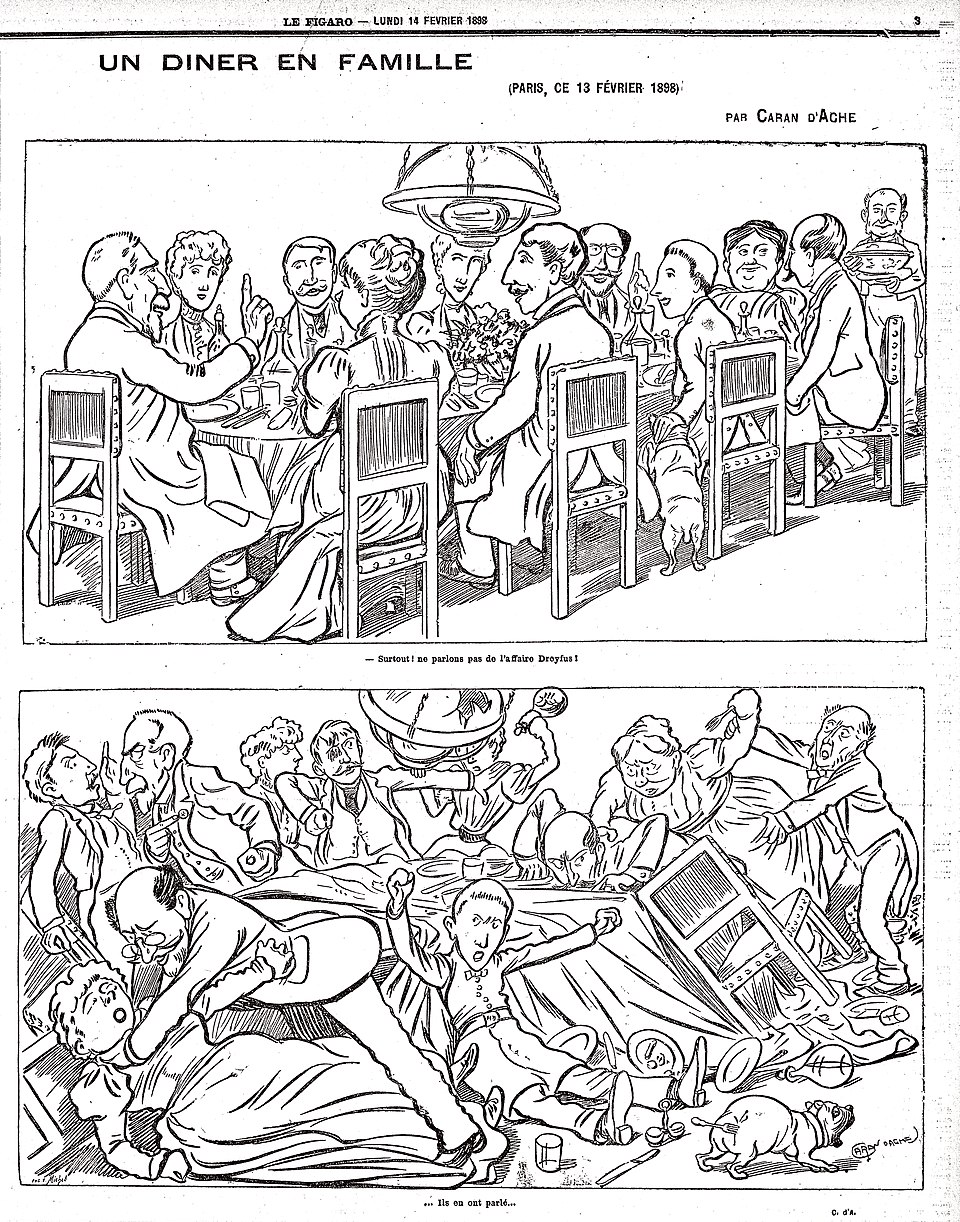

A bit like in that famous editorial cartoon published at the time of the Dreyfus Affair : a dinner table where people say, “Let’s not talk about it,” and then, in the next panel, they are fighting with each other, upending the table — and the caption reads, “They talked about it.”

So, since I cannot satisfy everyone, I have decided tonight… to disappoint everyone.

I will speak about politics, and at the same time I will not speak about it. I will avoid the subject, and at the same time speak of nothing else.

Yes, it is possible — and in fact, it is very easy to do. One only needs to do what rabbis have always encouraged their congregants to do : read the Torah. And more precisely, the passage of the Torah associated with the festival we are about to enter.

Because yes, year after year — whether or not there is a fall equinox that day, whether or not there is a United Nations General Assembly, with or without the recognition of a Palestinian state, with or without war in the Middle East, with or without a terrifying and exponential surge in antisemitism, with or without internal tension in our societies and in our communities, with or without all that — year after year, on Rosh HaShana, Jews have always read the same text, a surprising passage that seems utterly illogical to read today.

Just imagine for a moment that you had to decide which text ought to be read on the first day of the Jewish year in the synagogues. Where would you have begun the reading ? I am certain there are a variety of opinions in this synagogue.

There are those who think that, obviously, we should begin at the very beginning : read Bereshit and the Creation of the world, the opening of a new time for a new year. That makes sense !

Others reply : not at all ! One must read the biblical passage that speaks of Rosh HaShana, the excerpt that explains that on the first day of the month of Tishri we are to sound the shofar… now that is relevant !

Some would have said : but of course, we must obviously read the story of the Akedat Yitzhak, the binding of Isaac. It is the moment when we understand the meaning of the shofar, the horn of the ram that was sacrificed in place of Abraham’s son. That is the wisest choice !

And yet, tomorrow we will not read those texts. Rather, as every year, we will read chapter 21 of Genesis — a story that, at first glance, has nothing to do with Rosh HaShana, with a new beginning, or with the shofar. A disturbing story that I would now like to tell you once again.

Abraham had two wives — or rather, a wife and a concubine. The first was named Sarah, and she struggled to give birth to a son. Eventually he was born, and he was named Isaac. The second was named Hagar, and she bore a child to Abraham — his firstborn son — who was named Ishmael.

The rest of the story, you already know — and we will also read it tomorrow.

One day, Sarah was convinced that Ishmael was a threat to her son Isaac, whom he seemed to mock or mistreat. So she took radical action to protect her child, demanding that Hagar and her son be sent away into the desert.

Hagar too wanted to protect her son, but in the desert and without water, he was about to die. In despair, she stepped away for a moment and wept. And then a divine intervention saved him — the very same divine intervention that, a little later, would save Isaac from sacrifice.

Each year, on Rosh HaShana, we read the story of two children who might have perished, and the story of two mothers who wanted to save them — the story of people who, in the text, never speak to each other again.

Of course, these stories are painful to read today. One would have to be in complete denial not to feel their echoes : Isaac is seen as the ancestor of the Jewish people, and Ishmael as the ancestor of the Arab world.

On the first day of Rosh HaShana, among all the texts we might have read—texts that recount our story, our beginnings, our wounds or our hopes—it is this one that we are commanded to visit, or revisit : the story of the quintessential Other, and the way in which their destiny is interwoven with our own.

We read the story of a severed brotherhood, the story of hostility between mothers who simply want to protect their children, who banish another or who withdraw themselves when death prowls.

One of these women is named Sarah, from the Hebrew root shin-resh-hei (שרה), which gave, among other words, sar or sarah—a leader, a prince, or a princess—but also the name Yisrael, which has something to do with the strength of sovereignty and governance.

As for Hagar, the name of Ishmael’s mother, anyone versed in Hebrew knows it is spelled hei-gimel-resh (הגר), and everywhere else in the biblical text these three letters are read as ha-ger—“the stranger.”

Hagar is called “the stranger.” In her name she carries a root that appears again and again, dozens and dozens of times in the Bible, always with the same injunction :

- Exodus 22:20 — וגר לא־תונה ולא תלחצנו כי־גרים הייתם בארץ מצרים

You shall not wrong a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

- Exodus 23:9 — ואתם ידעתם את נפש הגר כי־גרים הייתם בארץ מצרים

You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt.

- Deuteronomy 10:19 — ואהבתם את הגר כי־גרים הייתם בארץ מצרים

You too must love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

You see, it is odd : on Rosh HaShana we are invited, through the figures of these two women, to think not only about what sets peoples against each other—Jews and Arabs, or any belligerents in a conflict—but perhaps also about two forces within us in conflict, two facets of our identity.

Abraham is bound to two women. In his life there is both the strength of sovereignty and the awareness of strangeness. And this constant tension between them is not without connection to what the Jewish people have experienced throughout their history.

Throughout history, the Jewish people have longed for a sovereignty that was denied them. Again and again, they have been Hagar—the stranger cast out into the desert toward certain death.

Today, in Israel, they are Sarah—sovereign and in a position to rule. There are many who continue to deny them this legitimacy and this right. But such legitimate sovereignty cannot exist without vital reflection on what it demands—above all, the remembrance of strangeness, the concern for the stranger.

Make no mistake : I do not wish to speak of politics. But on the day of Rosh HaShana, are we given the opportunity to speak of anything else ? Is it possible to do so when the passage chosen by our sages for this holiday is perhaps the most political of all ?

Tomorrow the shattered notes of the shofar will sound, that sound that stirs our innermost being, and we will read this text. And each of us must ask : Who am I in this story ? Which voice in this story echoes within me ? Is it the legitimate fear of Sarah ? Is it the supplication of Hagar ? Is it the call to protect a sovereignty that Sarah has at last attained ? Or is it the memory of the ger, the path of Hagar, which haunts our texts again and again ?

And all these questions dwell within us alongside other anxieties : the overlap of our holidays with the recognition of the State of Palestine ; the apprehension for the safety of our children ; our concern for the lives of the hostages, and for the lives of innocent Palestinian civilians who die each day ; our anxiety for a generation sent into combat, and for a region devastated by grief ; the fear for the values of the Republic, trampled daily by antisemitism. All of this propels us into this text more than in any other year—into the time of anxious mothers, into the time of impossible dialogues, into the time of nights that must be endured. All these banners fly, in our lives, simultaneously.

Allow me now to make an aside and speak of someone else. I have spoken of two mothers present in the text, and I would like to mention a third who does not inhabit the lines of the story.

This mother’s name is Dora. She was born in 1927 in France, into a family of Russian‐Polish origin. At the age of 15, she was deported to Auschwitz with her family, on convoy number 72. Upon arrival at the camp, she saw her mother and her little sister sent directly to the gas chambers. She herself was selected for labor, and there, in the camp, still a young girl, she formed a friendship with a girl named Simone and a girl named Marceline, who were exactly her age and who became her lifelong friends. She was one of those “girls of Birkenau” whose testimonies we read.

One day, Dora’s life was miraculously spared when Dr. Mengele had selected her. She had the strange impulse to stand up and begin to sing. She launched into a song by Edith Piaf, and that day she was pulled out of the line—and she survived.

After the war, she married and became the mother of three children and, later, of many grandchildren and great‐grandchildren.

She devoted her life to bearing witness, in high schools and in prisons. She refused to devote her life to vengeance or to the hellish cycle of anger. Again and again, she chose life.

I had not planned to speak of her today, but as it happened, this very morning at 11 a.m. in the Bagneux Cemetery, in a windswept alley, Dora was laid to rest, surrounded by her loved ones, and we told her story. And I could not let this evening pass without telling you a word about her.

Dora Goland joined her loved ones on the last day of the Jewish year 5785, and I do not wish to enter 5786 without recalling her memory.

This generation—the generation of Dora, of Simone, and of Marceline—is leaving us, but the challenge they bequeath to us survives them, and it is bound up with what we still must endure. With our anxieties, the violence that surrounds us, our pains and our traumas, we must find how, for our part, to choose life.

Listening this morning at the cemetery as Dora’s family sang, recalling how singing had once saved her and remained her source of resilience in life, I suddenly remembered a song…

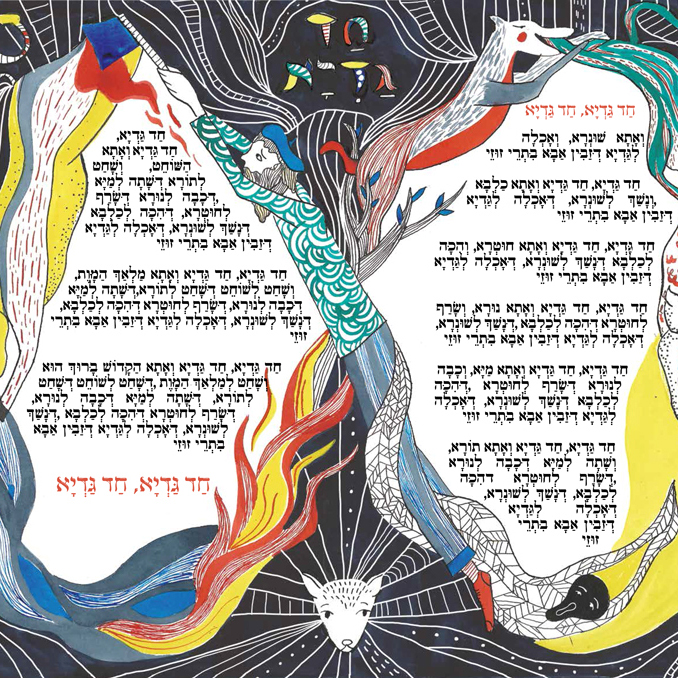

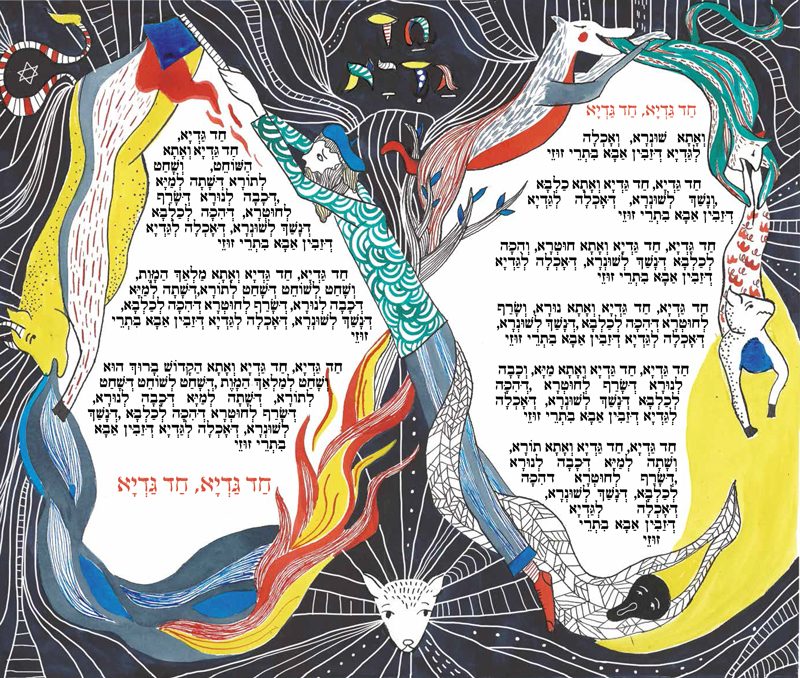

Not the Ma nishtana I whispered a little earlier, but another song that is sung on the night of Passover and is deeply connected to that holiday.

Remember its words : דאזבין אבא בתרי זוזי חד גדיא חד גדיא — dzabin aba bitrei zuzei, chad gadya, chad gadya — “My father bought a kid for two zuzim, chad gadya, chad gadya.”

The cat ate it, and the dog bit the cat and was beaten by a stick, which was itself burned by the fire. The fire was extinguished by the water, which was drunk by the ox, which was itself slaughtered by the butcher, before the Angel of Death took his life…

This terrible song, which we sing to a merry melody at Passover, is in fact the saddest of all. It tells the tragedy of vengeance and its morbid cycle—the way this infernal chain never comes to an end. There is always someone to strike another and avenge a third, only to become in turn a victim of the chain of violence, which eventually kills everyone and destroys everything in its path.

I know you see where I am going with this—both those who wanted me to speak of politics tonight, and those who especially did not.

In 1989, a very famous Israeli singer, Chava Alberstein, wrote an alternative version of Chad Gadya.

It was in the midst of the First Intifada, and amid violent events in southern Lebanon, that this popular singer revisited the liturgy of Passover and composed what turned into an anthem.

The song says : “My father bought for two zuzim one little kid, chad gadya, chad gadya…

Then came the butcher, who slaughtered the ox, that drank the water, that quenched the fire, that burned the stick, that beat the dog, that bit the cat, that ate the kid that my father bought for two zuzim.”

But at the end of the song she adds these words : “Why sing Chad Gadya today ? Spring has not yet come, and Passover has not yet arrived. Ma nishtana? And what got changed for us?”

“I,” says Chava Alberstein, “I got changed this year.”

She adds : “That all the nights, all the nights I asked only four questions, this night I have another question : Ad matai yimashekh ma'agal ha'imah ? אד מטאי יימשך מעגל האימה “until when will the circle of terror continue?” Chase and be chased, beat and be beaten, when will this madness be ended?”

Chava Alberstein writes :

“I was once a sheep and calm kid

Today I'm a tiger and a wild wolf

I've already been a dove and a deer.

Today I don't know who I am.”

And this is the question I ask us tonight : Who are we ? Who are we preparing to become in the year now opening before us ? Will we be those who listen to Sarah’s fear, or to Hagar’s tears—or those who know how to hear them both ?

Those who guard a rightful refuge, those who also know what they owe to the stranger they once were ? Those who remember that we were lambs no one wanted to defend, those who fear becoming wolves who no longer recognize themselves…

Today, do we truly know who we are ?

Ma nishtana ha-laylah hazeh מה נשתנה הלילה הזה — in what way must this night, more than any other, help us to ask ourselves these questions with utter seriousness ?

And because, like Dora, I believe that sometimes a song can quite literally save our lives, I would like us to listen to this Israeli song and to tell ourselves that perhaps it was written for this very evening—that this night, unlike any other, might allow us, once more, to choose life.

Translation by Antoine Strobel-Dahan